The mathematics are unforgiving. Despite decades of corporate sustainability initiatives, natural habitat loss continues at an accelerating pace. The much-vaunted 2030 target to protect 30% of Earth's natural systems appears increasingly fictional. Traditional ESG frameworks, for all their good intentions, have proven structurally inadequate to the task of genuine ecological preservation.

This is why we developed APres—the Adaptive Planetary Resilience Exchange System—a business model that abandons the familiar rhetoric of "doing less harm" in favour of something more radical: active stewardship as a prerequisite for commerce itself.

APres is a framework for designing business models that operate within—not beyond—the Earth's ecological limits.

What is the APres model?

The APres Model: A Blueprint for Responsible Business

How Wide Open World is pioneering a new framework that places ecological stewardship at the heart of commerce

The Indigenous Logic of Business

At its philosophical core, APres draws from indigenous thinking that views economic activity through the lens of intergenerational responsibility. The model applies what's known as the "seventh generation test"—evaluating every business decision against its impact on seven generations hence. It's a concept that sounds almost quaint until you grasp the science behind it.

"The relentless pursuit of efficiency has created a fundamental blindspot," explains Olivier Maréchal, who developed APres in 2023 as part of his research at Warwick Business School. "We've optimised for scale and output while treating ecological boundaries as externalities. APres makes those boundaries central to business viability."

The framework addresses what economists have long acknowledged but never systematically quantified: the economy's dependence on natural capital. Scottish economist Adam Smith understood that nature underpins wealth; Ecological economist Herman Daly highlighted the economy's failure to recognise safe ecological load limits. APres provides the missing blueprint—a way for free markets to function without overshooting planetary boundaries.

Beyond Carbon Theatre

Most sustainability strategies fall into predictable traps. They prioritise efficiency over ecological stability, focus on reducing harm while expanding production, and treat carbon neutrality as the ultimate goal while ignoring broader ecosystem impacts. APres takes a fundamentally different approach.

Rather than chasing carbon neutrality—which the model considers conceptually flawed given that fossil carbon cannot be meaningfully offset except through permanent storage—APres adopts a holistic approach to the biodiveristy and climate challenge. It centres on direct habitat preservation to prevent unconstrained growth while deploying an internal carbon tax to accelerate investment in low-carbon solutions. The logic is elegant: for every hectare used in production, a scientifically determined amount must be preserved within the same ecological region, while carbon tax revenues maximise incentives for the transition to a low-carbon economy.

This isn't feel-good environmentalism. The calculations follow rigorous peer-reviewed guidelines that split responsibility for maintaining planetary boundaries between state and private actors. If governments meet potential forest cover targets (85% for boreal and tropical forests, 50% for temperate) by putting them under state protection, private actors don't need to contribute financially. If forest cover targets are not met and forests are not protected, businesses must contribute directly to their preservation. A similar logic applies to biosphere integrity. The biosphere requires land to function—too much appropriation and conversion by human society threatens fragile ecological equilibrium. For every fraction of land taken by economic activity, a scientifically determined portion must be protected. Otherwise, we risk witnessing nature's disappearance.

How We Apply APres at Wide Open World

Wide Open World serves as APres's first real-world application. Each jumper in our collections funds approximately 200 square metres of habitat preservation: 100 square metres through on-farm conservation and another 100 through permanent protection via our partnership with the Tasmanian Land Conservancy.

The model's sophistication lies in our accounting treatment. Conservation obligations appear on our balance sheet as liabilities, receiving the same scrutiny as financial obligations. Independent scientific partners manage conservation efforts, ensuring decisions prioritise ecological needs over commercial interests.

Our approach demonstrates that businesses can do more than reduce harm—we can actively protect what sustains life itself.

A new logic for sustainable business

APres introduces a radical evolution from conventional business thinking: constrained growth. When land is fully under stewardship, expansion becomes ecologically irresponsible—and the model's scoring reflects that reality.

This constraint mechanism extends beyond land use to freshwater flow and chemical pollution. Rather than allocating specific quotas, which is impractical and rife with bias, APres drives regional discussions among economic actors when ecological boundaries approach critical thresholds. It's polycentric governance by design—acknowledging that business decisions must account for cumulative regional impacts.

The financial implications vary by sector and intensity of land use, but the model doesn't favour volume-driven strategies over smaller, differentiated actors. That distinction matters because the pursuit of aggregate economic growth while reducing footprints favours production intensification—a significant market failure. With APres, businesses that generate more value with smaller footprints maintain advantages, while small-scale businesses preserve their differentiation. It's not either-or: stewardship obligations are fairly and proportionally calculated.

Moving Beyond Traditional Sustainability

What distinguishes APres from existing sustainability frameworks is its rejection of marginal improvements in favour of absolute boundaries. Traditional ESG metrics allow companies to improve efficiency while expanding overall resource consumption—the classic Jevons paradox that efficiency gains often increase total consumption.

APres sidesteps this trap through its "Value-Harm Nexus," which makes ecological impact an explicit factor in every business decision. Companies must evaluate their materials, production methods, and ecological footprints through specific principles: land use preservation, chemical pollution limits, ecosystem integrity, rejection of intensification, and ethical value propositions.

The model establishes "Stewardship Funds" that ensure businesses contribute directly to conservation while channelling carbon tax investments toward low-carbon technology adoption at scale. It's a framework that treats sustainability not as competitive strategy but as a precondition for responsible operation.

The APres Evaluation System

APres redefines sustainability through three interconnected scores:

- Biosphere: Land conservation as a first-order priority, ensuring that economic activity doesn’t outpace nature’s ability to regenerate. Novel entities (chemical pollution, including from synthetic materials) and freshwater quality are also evaluated against defined limits.

- Atmosphere: A carbon tax mechanism to reduce emissions and leverage the investment flow to accelerate the shift to a low carbon economy. A rejection of the idea that fossil carbon can be offset by plantings, a notion that is unfortunately driving unprecedented public disinformation. Ozone and aerosols are also evaluated against defined limits.

- Hydrosphere: Direct river flow monitoring and evaluation, driving regional accountability to manage a shared precious resource.

Why We Share This Framework

Questions inevitably arise about whether APres can scale beyond fashion to industrial-scale operations. That question misunderstands the model entirely. It's not about expansion—it's about preservation.

"Focusing on product-level efficiency metrics favours intensification but does nothing to protect what should remain," Maréchal notes. "APres is the first model that internalises negative externalities to directly fund preservation. We're moving from unconstrained growth to growth that accounts for ecosystem-specific needs. Or, put differently, we're not scaling harm more slowly—we're scaling stewardship."

The fundamental insight is that before addressing global ecological overshoot, we must stop overshooting. Protecting what should remain creates productive tension between economic growth imperatives and ecological preservation—a tension that current markets systematically avoid.

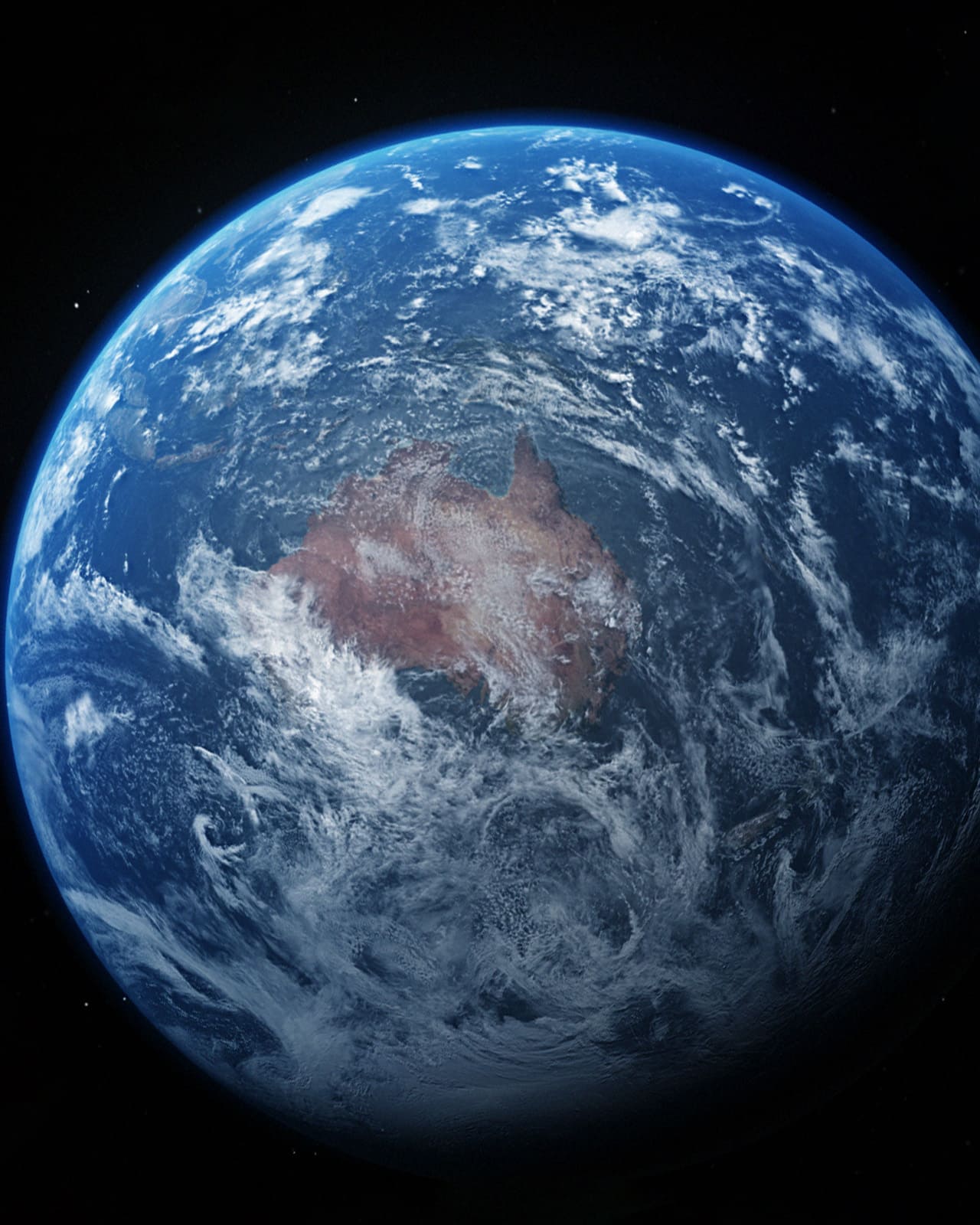

"Take planet Earth. Imagine we halve its diameter overnight. Clearly, this would create more than just a problem to grow the economy. Now imagine we double its diameter. We might have room to grow. A wise civilisation would want to grow, absolutely, but it wouldn't be blind to its stewardship obligations. Today the narrative is growth. Limits remain taboo. It's time to evolve," reflects Maréchal.

A Framework for the Future

APres isn't confined to fashion or even the agriculture, forestry, and land use sectors where it most naturally applies. The model provides a template for any business whose operations intersect with ecological boundaries—which, ultimately, includes virtually all commerce.

We've made the APres framework available through the Natropy consultancy, rejecting the notion that sustainability should provide competitive advantage. The logic is straightforward: if the model works, withholding it undermines its fundamental purpose.

As global ecological indicators continue their alarming trajectories, APres offers something increasingly rare in sustainability discourse: a concrete alternative to business as usual. It's a framework that treats the natural world not as an input to optimise but as a partner whose interests must be explicitly protected.

At Wide Open World, we believe this represents the future of responsible commerce. The real question isn't whether we can afford ecological constraint—it's whether any economy can survive without it.

When you buy from Wide Open World, you're not just purchasing exquisite knitwear—you're embracing stewardship principles, protecting 200m² of wild land where the fibres come from. You are helping redefine commerce. Thank you.