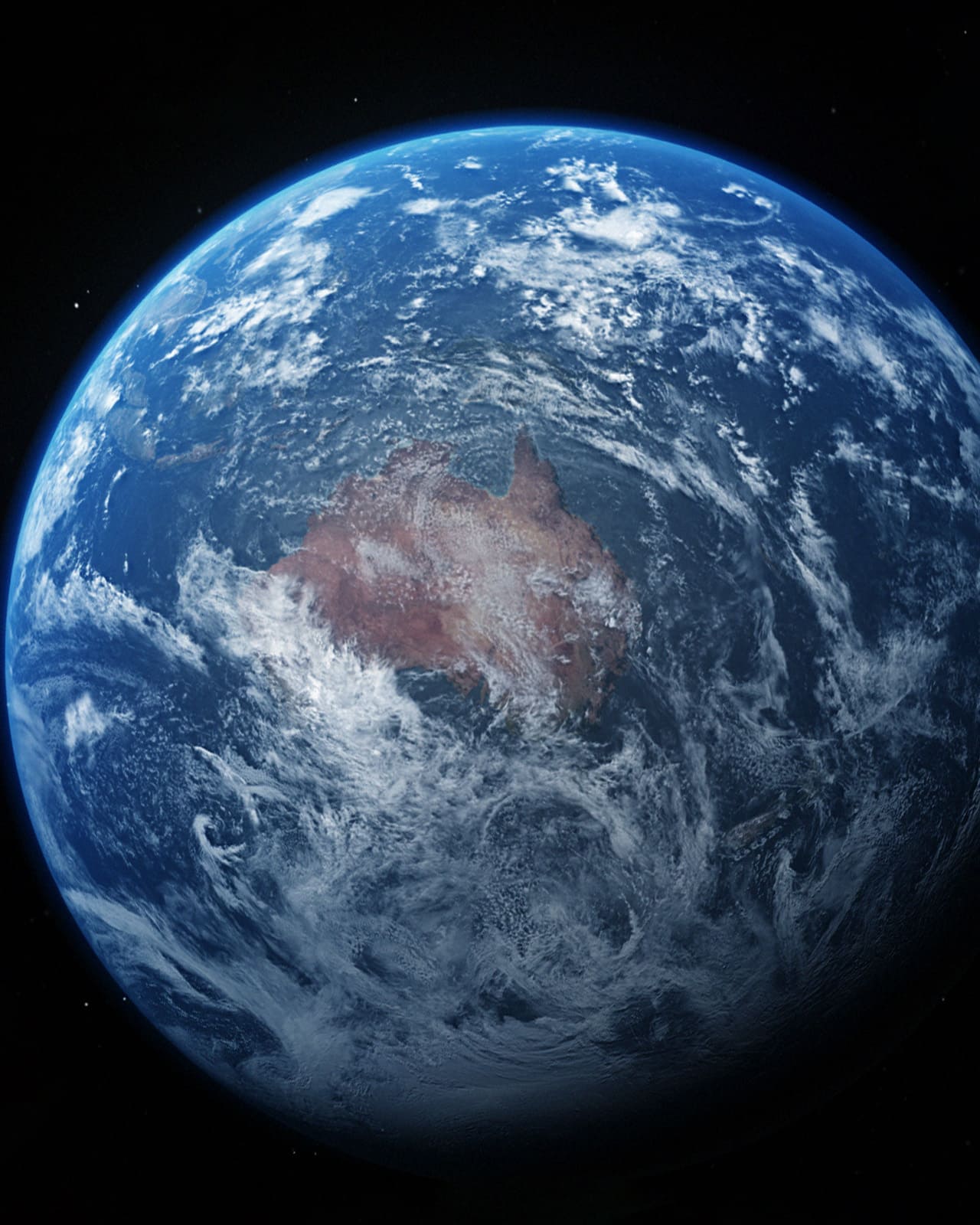

Sustainability has become a powerful narrative. It’s everywhere—woven into marketing campaigns, product labels, and corporate missions. But behind this buzzword often lies a veneer of half-truths, masking scientific realities.

At its core, true sustainability means addressing the systemic issues driving the ecological crisis. When we confront the reality about the physical world that surrounds and supports us, we realise that sustainability is simply about maintaining the environment in a stable state. The first order consideration is not about philosophical ideals. It is about sustaining the life-support system nature offers.

Yet many popular solutions oversimplify these challenges, focusing on surface-level fixes rather than transformative change.

Let’s examine five of the most pervasive myths and why they fall short.

Myth 1: Reducing impact per product is more sustainable

Efficiency metrics can mask a profound and insidious problem. Reducing resource consumption or emissions per unit does not equate to genuine sustainability—it often conceals a more troubling reality since reducing impact per product is the definition of production intensification.

The limitations of incremental approaches become clear when examined critically:

- Production Intensification: Marginal efficiency gains frequently drive increased production, ultimately worsening the total ecological strain

- Narrow Perspective: Focusing on unit-level improvements obscures the fundamental need to preserve entire ecosystem integrity

- False Narrative: Incremental reductions create an illusion of progress while failing to address root systemic challenges

Redefining Ecological Responsibility

Sustainability is not about minimising harm—it's about active restoration and preservation. True progress requires a holistic approach that prioritises ecosystem health over marginal production efficiencies.

Carbon emissions exemplify this challenge. Phasing down fossil fuels demands more than isolated product assessments. The critical lens is not the carbon footprint of a single item, but the cumulative impact of total production volume—a perspective that exposes the limitations of per-unit efficiency metrics.

Our commitment transcends footprint reductions. We aim to design systems that regenerate, protect, and elevate the natural world. Where others seek volume, we seek harmony.

Myth 2: Recycled plastics are sustainable

The narrative of transforming plastic bottles into clothing has become a convenient sustainability myth—an elegant soundbite that obscures the reality.

Plastics—whether virgin or "recycled"—carry a toxic legacy. Derived from petroleum, these materials persist for generations, leaching harmful chemicals and shedding microplastics that contaminate marine ecosystems and human health.

Contrary to popular belief, plastic recycling is neither simple nor effective:

- Less than 10% of global plastic production is recycled

- Most plastics can only be recycled once

- Converting bottles to clothing eliminates their potential for future recycling, essentially abruptly shortening the useful life of the base material

The solution isn't about finding new uses for plastic, but fundamentally reimagining our approach to materials. True sustainability demands materials that integrate harmoniously with natural systems—not those that merely extend a destructive cycle.

Myth 3: Natural crops are sustainable

The assumption that natural fibres are inherently sustainable oversimplifies the ecological reality. Sustainability is not defined by the origin of a material, but by its relationship with the broader ecosystem. The true measure of responsible production lies in understanding and respecting the delicate balance of natural systems.

Sustainable crop production demands a rigorous approach that considers:

- Water Resources: Crop cultivation must not compromise local water systems, potentially draining critical aquifers and watersheds.

- Land Use: Agricultural expansion cannot come at the cost of natural habitats, threatening biodiversity and ecosystem integrity

- Chemical pollution: Agricultural practices must minimise ecological disruption, preventing soil degradation and broader ecosystem harm

The fundamental question is not to compare the footprint of products (which says nothing about ecosystems), but how much can be produced while maintaining the planet's ecological equilibrium. Sustainability requires more than good intentions—it demands a scientific approach that places ecosystem preservation at the core of production.

Myth 4: Planting trees equals carbon neutrality

Carbon neutrality has become a convenient narrative for brands seeking environmental absolution. Yet, the mechanism of claiming neutrality reveals a deeply flawed approach to environmental sustainability.

The carbon compensation model breaks down at multiple critical points:

- Geological Time Disruption: Fossil fuels represent carbon safely stored over millions of years, released instantaneously through human activity—a reversal of geological processes happening overnight

- Atmospheric lifetime: Excess atmospheric carbon persists for thousands of years, creating long-term planetary warming beyond immediate mitigation

- Temporary Carbon Storage: Trees sequester carbon temporarily, with no guarantee of long-term retention. If destroyed, stored carbon rapidly re-enters the atmosphere

- Ecosystem Fragmentation: Many planting initiatives rely on monoculture plantations, directly harming biodiversity and soil health to provide a good carbon story

- Legal Vulnerability: Without permanent land covenants, there are no assurances that planted forests will remain protected. Current standards provide minimal safeguards, failing to establish binding, intergenerational obligations that would genuinely secure ecological preservation.

What this strictly means is that carbon neutrality is the wrong term to express the work. In reality, it is a laudable step, done to augment short-term carbon sequestration, with little to no long-term benefits and ethical guarantees. It doesn't solve the fossil fuel problem.

Reimagining Environmental Stewardship

Real solutions prioritise protecting existing natural ecosystems, not creating engineered quick fixes. When the focus is on active preservation and restoration of the planet's delicate ecological balance, carbon sequestration initiatives are important. When the focus is on maximising profits per tonne sequestered, businesses need to look away.

Our approach transcends carbon accounting. We seek to design systems that protect, not merely offset. We also prioritise partnership with NGOs that share our vision of protecting land on perpetuity.

Myth 5: Animal farming is not sustainable

Animal farming is an emotive topic which demands a nuanced, scientifically grounded perspective. Simplistic assertions about sustainability fail to capture the intricate ecological dynamics at play.

Scientific evidence shows the reality is not all black and white:

- Ecosystem Interdependence: Grazing animals play a critical role in maintaining ecological balance, particularly in extensive grass-fed systems

- Systemic Variations: Intensive farming differs fundamentally from extensive systems. Intensive farming is not animal or environment friendly.

- Deforestation Drivers: Intensive animal farming contributes significantly to habitat destruction, particularly in regions like Brazil where feed production encroaches on natural landscapes

“Sustainability is not about product impact. It is about what we leave behind, in ecosystems.”

The Ecosystem Imperative

Sustainability is not determined by farming method alone, but by the degree to which agricultural practices preserve ecosystems, especially untouched natural habitats.

No single approach offers a universal solution. The path forward requires an understanding that prioritises ecosystem preservation over simplified narratives.

Unfortunately, this is almost never the case since most people think in terms of product footprints, not ecosystems.